New to Assessment?

First time exploring the field of assessment? Fear not. We put together a collection of open-access resources introducing the basics of assessing student learning. We recommend starting here, and then exploring and supplementing these resources with materials that are relevant to your specific practice questions and audiences.

Conversations around assessment, akin to higher education in general, can quickly become jargon filled. Thus a good starting point involves an overview of key terms and acronyms.

Our Acronym List takes the guess work out of what the acronyms for which accrediting agencies and assessment-related organizations stand. It is not an exhaustive list, but does provide a quick, painless reference point.

Our Assessment Glossary contains definitions to terms and concepts you are likely to encounter in assessment literature, practice, conferences, and conversations.

Our Assessment Journal list provides an overview of scholarly journals and sources of information on assessment related literature.

We also have a list of Assessment Related Technologies detailing different software solutions that can meet your assessment needs. As well as additional resources that can be useful as you begin to delve into the assessment landscape including listservs, blogs, and communities of practice.

Activity: What is Your Philosophy of Assessment?

Knowing the philosophical stances of people, disciplines, units or departments on assessment can help improve communication and lower misunderstanding. This activity is designed to enable assessment professionals, and faculty and staff within departments and units, to know which philosophies they are aligned with to help them approach different conversations and communicate about assessment to different groups based on different perspectives.

Without clarity on the philosophy behind assessment, faculty and staff can talk past each other, misunderstand one another, and/or reinforce or obfuscate assessment culture. This activity can serve as a useful tool to explore perceptions and philosophical approaches regarding the purpose and value of assessment.

Activity: What is Your Student Affairs Philosophy of Assessment?

The activity presents a structured exercise to explore what student affairs practitioners believe to be true about the role and purpose of assessment as well as the best means to document student learning in relation to four philosophies: co-curricular learning, measurement of participation/satisfaction, compliance/reporting, and student-centeredness. Done individually or as a group, this activity can support internal communication and strategic planning on assessment

While most institutions will have information on writing learning outcome statements on an assessment website or center for teaching and learning website, we have compiled a sampling of a few different resources on various perspectives and approaches to writing learning outcome statements.

- A Brief Introduction to Creating Learning Outcomes by NILOA coach, Joe Levy

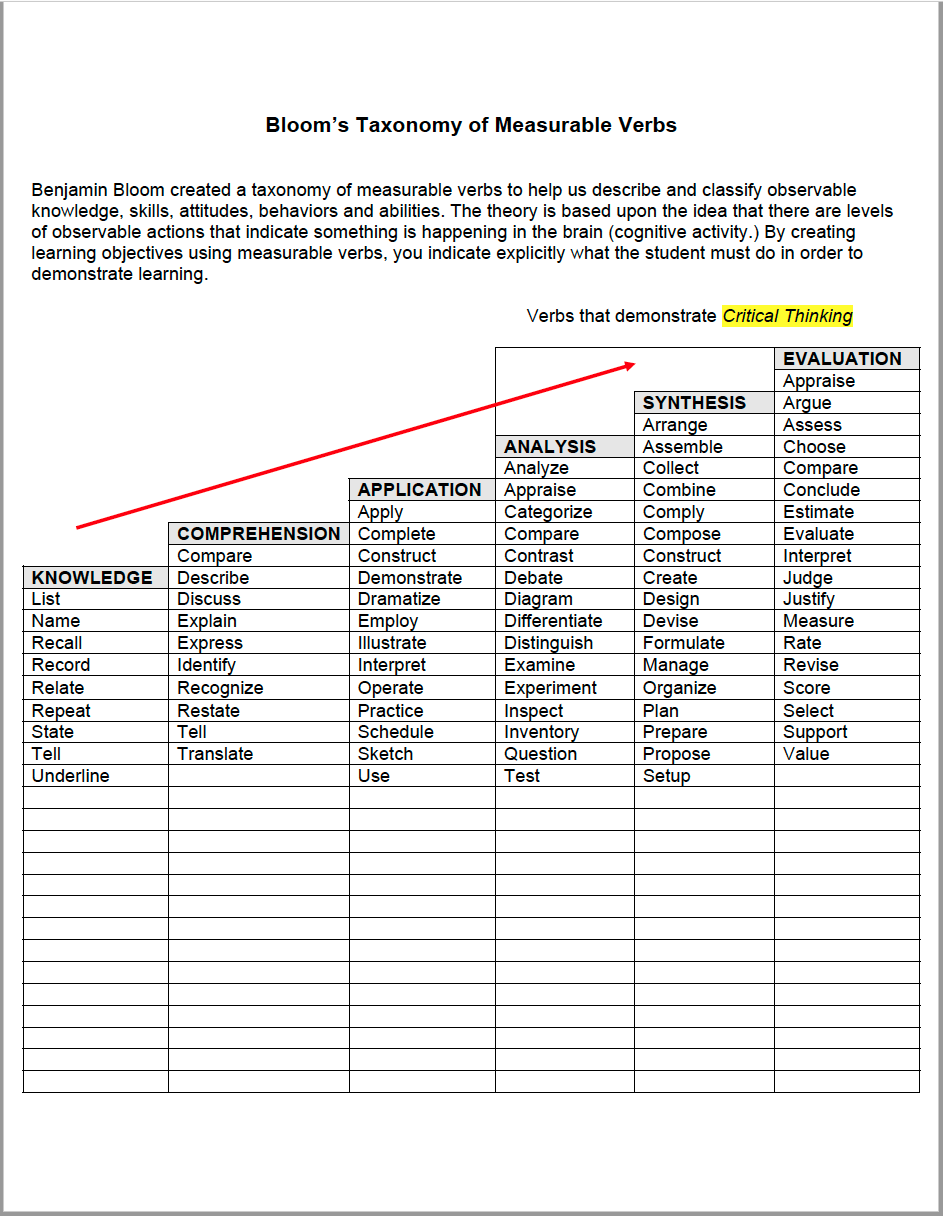

- Verbs that are useful for writing learning outcomes

- Bloom’s Taxonomy and the Revised Taxonomy

- Operational Verb List by Cliff Adelman

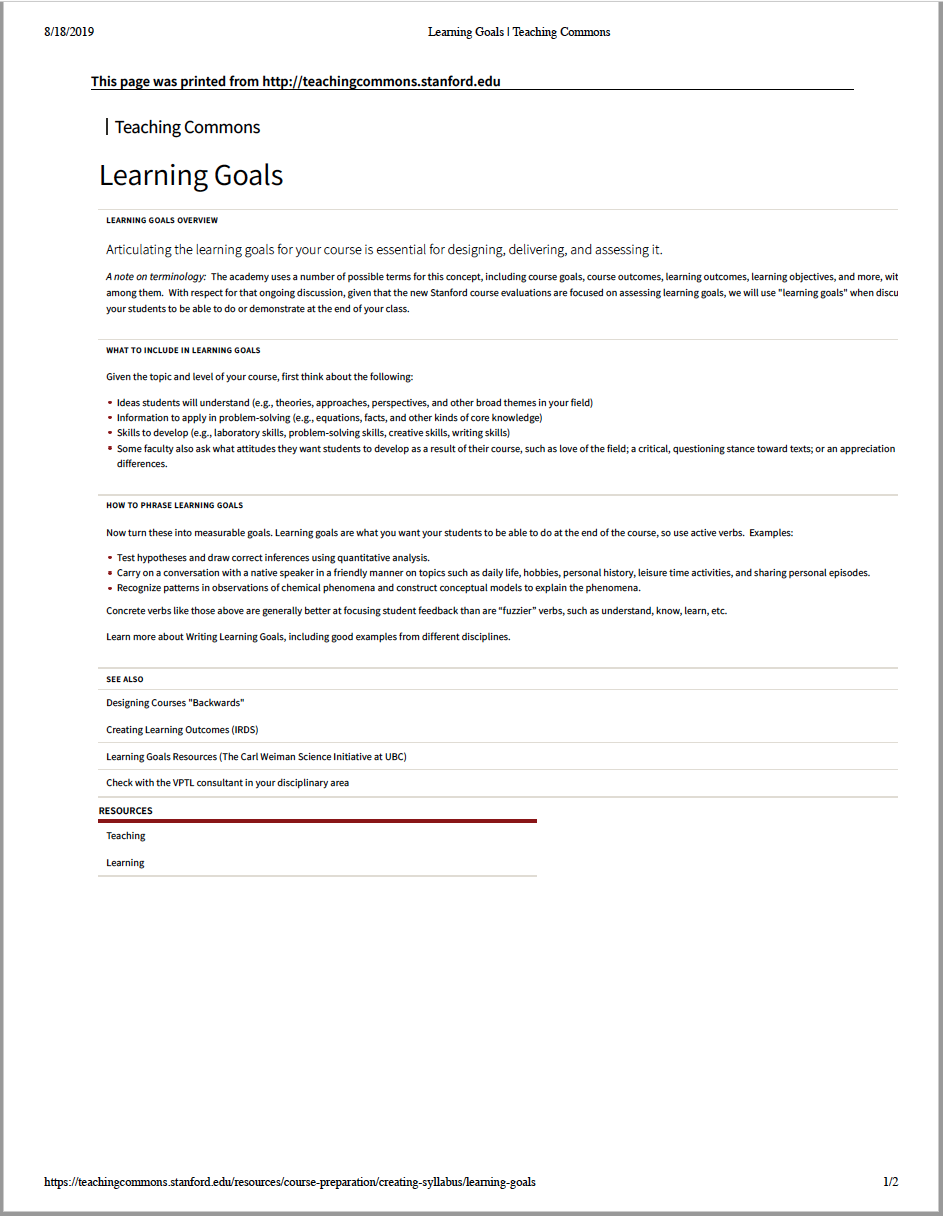

- Learning Goals and Their Role in Course Design

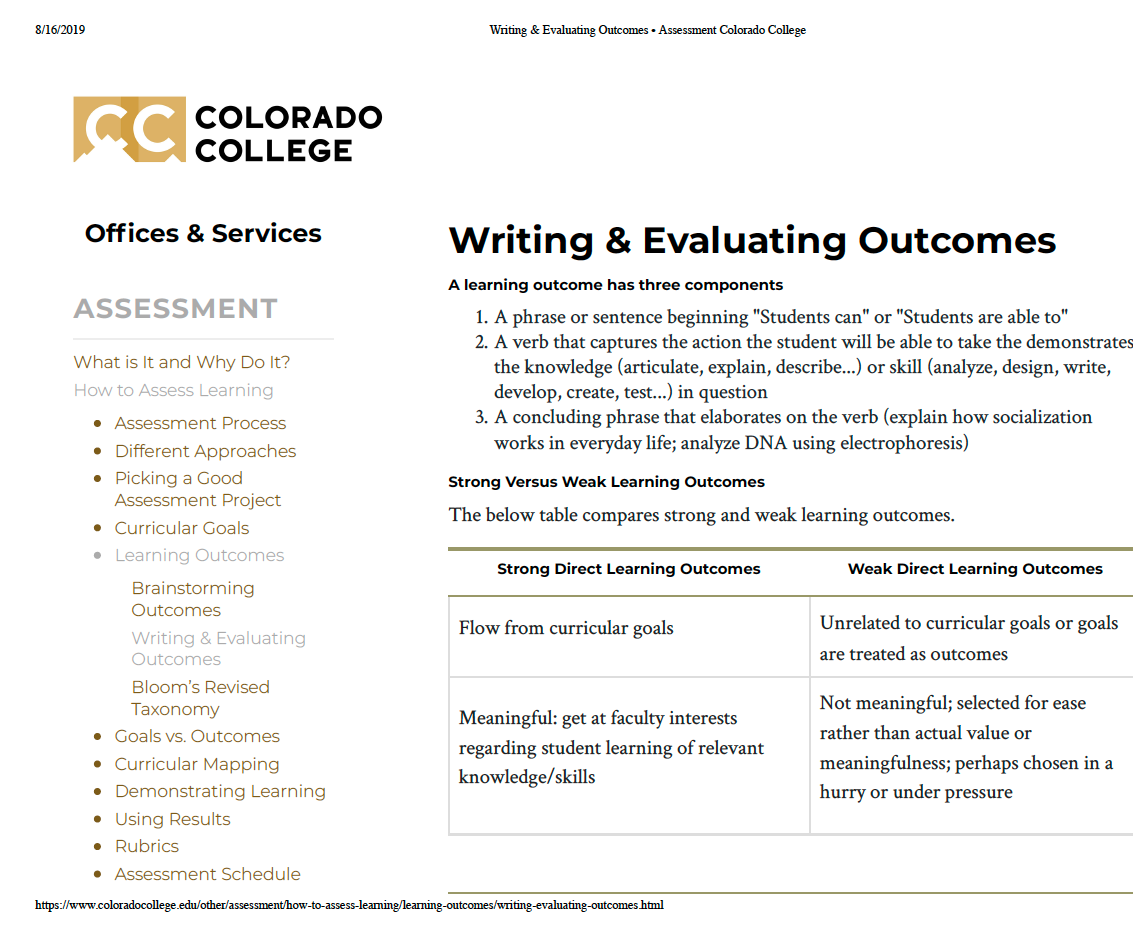

- Evaluating the Strength of Learning Outcomes

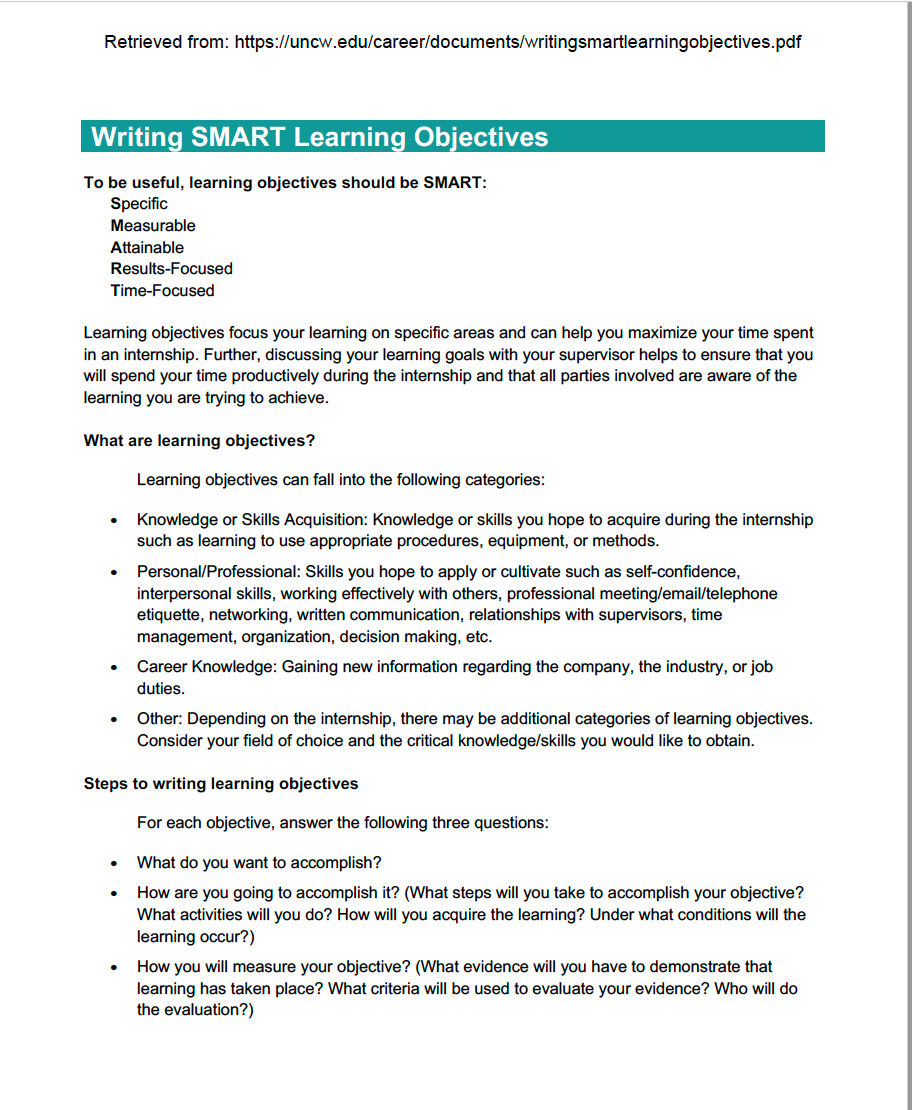

- Information on Writing SMART Learning Outcomes

The following resources provide a foundational understanding of assessment to inform the way you approach assessment work. Included are discussions on accreditation, assessment for accountability vs improvement, sources of evidence, and the relationship between assessment and pedagogy.

- A Brief History of Assessment

- Assessment, Accountability, and Improvement: Revisiting the Tension

- Regional Accreditation and Student Learning Outcomes: Mapping the Territory

- Higher Education Quality: Why Documenting Learning MattersÂ

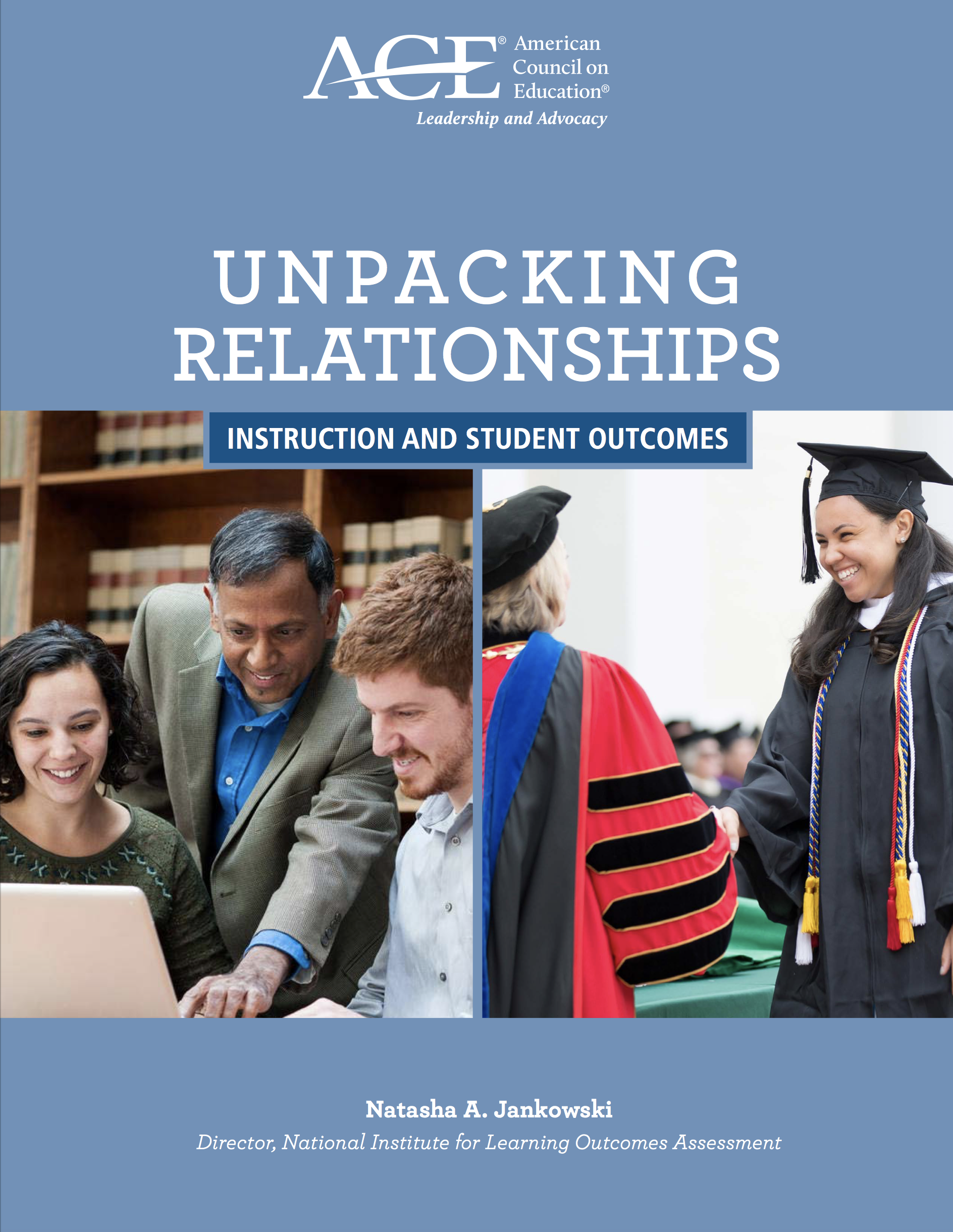

- Unpacking Relationships: Instruction and Student Outcomes

- Changing Institutional Culture to Promote Assessment of Higher Learning

- Using Evidence of Student Learning to Improve Higher Education

In order to know where you are going, we think it is helpful to know where we’ve been and currently are as a field. These resources provide an overview of the assessment landscape using findings from three iterations of a national NILOA survey of provosts, and more.

- Assessment that Matters: Trending toward Practices that Document Authentic Student Learning

- Knowing What Students Know and Can Do: The Current State of Student Learning Outcomes Assessment in US Colleges and Universities

- More than You Think, Less than We Need: Learning Outcomes Assessment in American Higher Education

- NILOA at Ten: A Retrospective

Simply transplanting assessment practices from another institution into yours does not mean they will yield similar results. However, the lessons learned and questions asked along the assessment process can be adapted to fit your context. The following examples provide thoughtful examples and considerations to make when conducting assessment and using evidence for improvement.

- Assessment 2.0: An Organic Supplement to Standard Assessment Procedure

- Using Assessment Results: Promising Practices of Institutions that Do It Well

- All-in-One: Combining Grading, Course, Program, and General Education Outcomes Assessment

- A Simple Model for Learning Improvement: Weigh Pig, Feed Pig, Weigh Pig

- Using ePortfolio to Document and Deepen the Impact of HIPs on Learning Dispositions

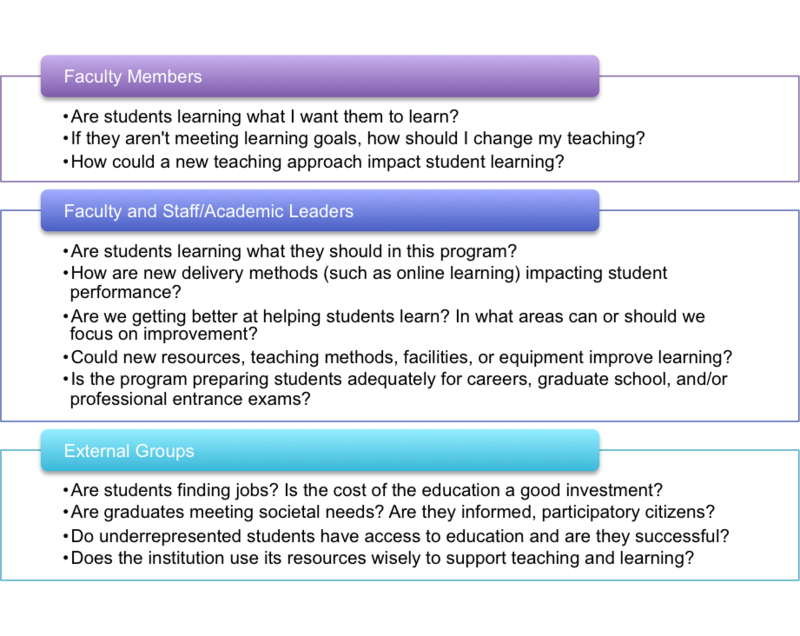

There are various stakeholders whom play a role in assessment. The following resources provide insight on considerations different stakeholders should make in assessment.

- What Faculty Need to Know About Assessment

- What New Student Affairs Professionals and Those New to Assessment Need to Know

- Governmental Policy and the Systemic Assessment of Student Learning

- The Governing Board’s Role in Assessment

- What Students Need to Know About Assessment

- A Portrait of the Assessment Professional in the United States:

Results from a National Survey - Gaining Ground: The Role of Institutional Research in Assessing Student Outcomes and Demonstrating Institutional Effectiveness

- Creating Student-Centered Learning Environments and Changing Teaching Culture: Purdue University’s IMPACT Program

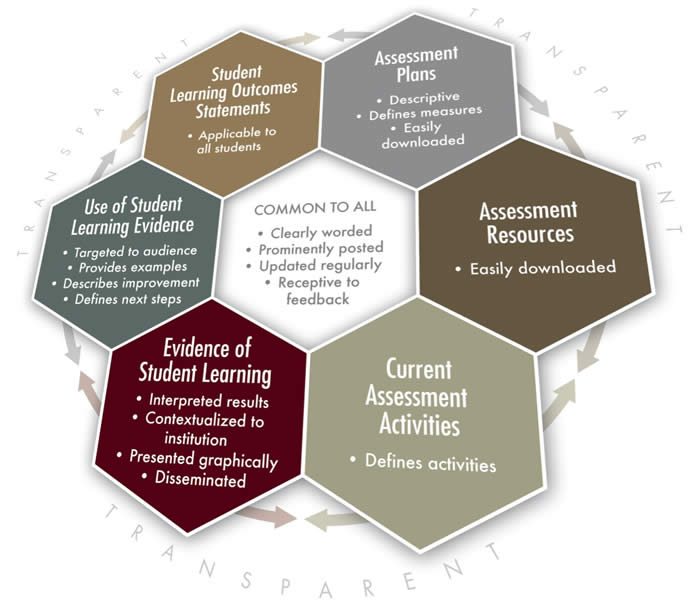

A significant element of assessment is transparency: sharing assessment data with various stakeholders and being open about the process. The following resources can help focus your thinking around transparency as it relates to assessment.

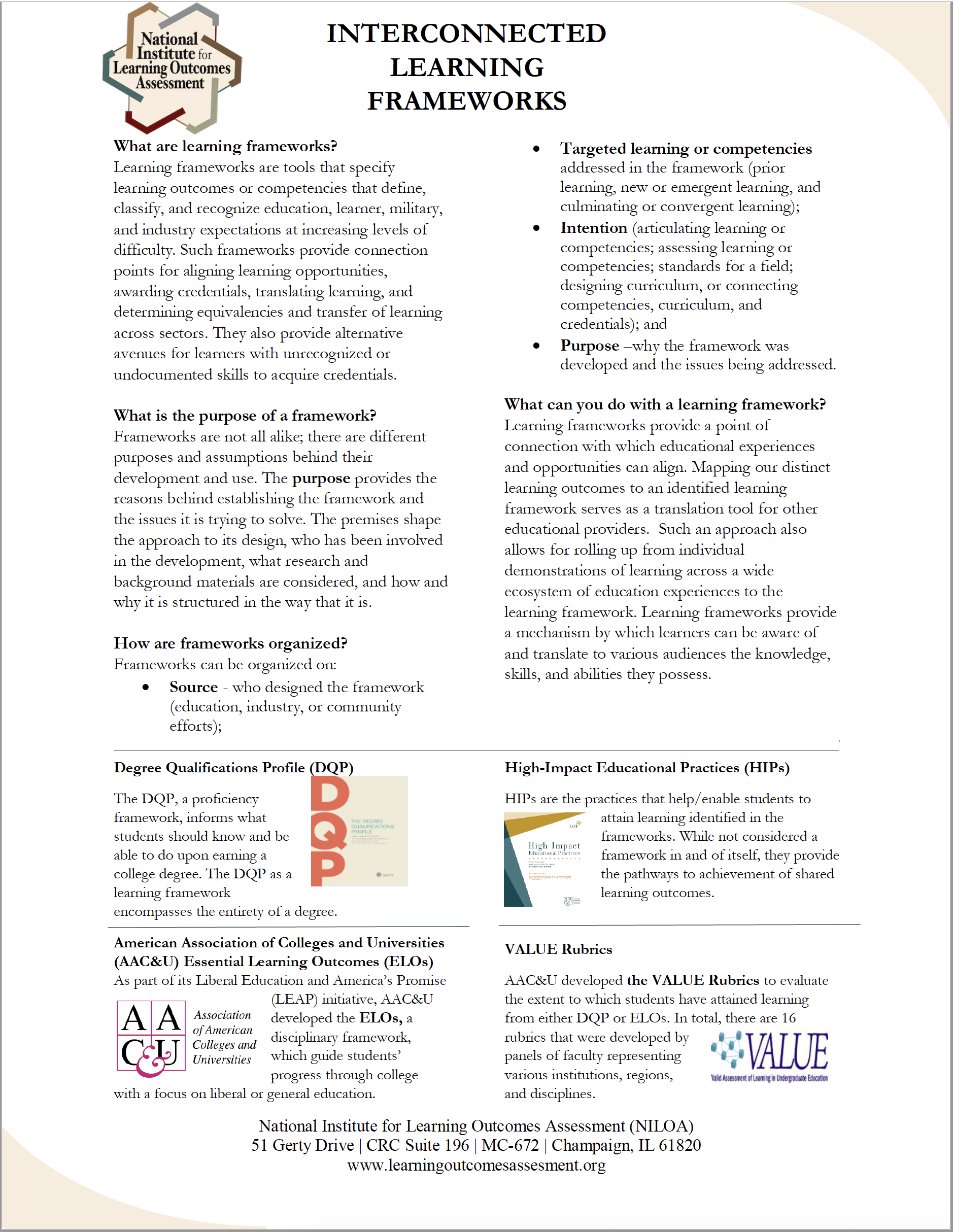

Learning frameworks are tools that help specify learning outcomes or skills that learners have acquired while facilitating their transfer from one context to the next. Learning frameworks play an important role in determining what students know and can do. The following resources provide an overview of learning frameworks and their relation to assessment.

- Interconnected Learning Frameworks

- Learning Frameworks: Tools for Building a Better Educational Experience

- The Degree Qualifications Profile: What It Is and Why We Need It Now

- The Lumina Degree Qualifications Profile (DQP): Implications for Assessment

- Using the Degree Qualifications Profile to Foster Meaningful Change

- Tuning: A Guide for Creating Discipline-Specific Frameworks to Foster Meaningful Change

Assessment Modules

Seven New England colleges and universities formed the Learning Assessment Research Consortium (LARC) and developed online modules on assessment to be utilized for professional development within colleges and universities nationally. NILOA is pleased to house the great work of the Consortium on our website. All LARC developed materials and module content are under a creative commons license.

Background: LARC is comprised of seven colleges and universities in New England that first came together during a “think tank” event. These institutions include: Suffolk University, Simmons University, Fitchburg State University, MGH Institute of Health Professions, Manchester Community College, St. Michael’s College, and Framingham State University. Four authors from the consortium: Chris Cratsley (Fitchburg State University), Jennifer Herman (Simmons University), Linda Bruenjes (Suffolk University), and Victoria Wallace (MGH Institute of Health Professions)”familiar with multi-day course design institutes™, developed a set of customizable online assessment modules to meet the needs of administrators, deans, chairs, faculty, and staff assessing student learning at the institutional, program, and course levels. Thanks to a generous grant from The Davis Educational Foundation, LARC completed a three-year project to develop six modules on a variety of topics related to assessment: Benefits & Barriers, Demystifying Assessment, Goals & Objectives, Gathering Data, Use of Assessment Data, and Sustainable Practices. In year three of the grant, the consortium partnered with NILOA as a platform for free online access, making these modules readily available. LARC and NILOA are continuing to explore ways to help institutions use these modules to create sustainable assessment practices on their campuses.

Introduction

Benefits and Barriers Facilitation Guide

Intended Audience

This module offers an introduction to the concept of assessment in higher education. It is intended for:

- Faculty at all levels; and/or

- Staff, administrators, as well as other institutional stakeholders.

Goals

This module is designed to help participants:

- Understand the benefits of assessment for different constituencies associated with your institution.

- Recognize the potential role of assessment data in decision-making across different levels of your institution.

- Explore the uses of assessment data for institutional improvement and accountability in your own role at your institution.

- Predict the common concerns and challenges that arise when institutions engage in the process of assessment.

- Envision how to better support and maintain the assessment process as a cycle of inquiry in your role at your institution.

![]()

Objectives

Upon completion of this module, participants will be able to:

- List various benefits of assessment for students, instructors, and other institutional stakeholders.

- Identify the impacts of the assessment process at various instructional and institutional levels.

- Describe how assessment is useful for institutional improvement.

- Recognize best practices for effectively using the assessment process to make evidence-based decisions.

- Categorize common barriers to effective assessment.

- Choose appropriate responses to common barriers of effective assessment.

Chapter 1: Benefits of assessment

![]()

Warm Up Activity: Write as many benefits of assessment as you can think of in one minute.

Were you able to come up with more than ten? Are these benefits things you have experienced or just read about?

![]()

The video shares the experiences of different faculty members and administrators on the benefits of assessment to improving teaching and learning in each of their respective roles.

While and after watching the video, write reflective responses to, or with colleagues discuss the following questions:

- What were some of the key themes that you heard/saw in the videos?

- Which benefits on your list were also mentioned by the faculty and administrators in the video?

- Which benefits mentioned in your video were not on your initial list? Did these benefits surprise you? If so, why?

- What differences did you notice in how the different types of positions (director of assessment, dean or chair, and faculty member) benefited from assessment? How did they use data similarly or differently?

If you have generated additional ideas after watching and reflecting on the video, please add them to your initial list.

![]()

Research on the Benefits of Assessment: Three Common Results from Assessment

In her book, Assessment Clear and Simple (2010), Barbara Walvoord explains that the three most common actions (or benefits) resulting from assessment are:

- “Changes to curriculum, requirements, programmatic structures, or other aspects of the students” program of study

- Changes to the policies, funding, and planning that support learning

- Faculty development (p. 5).

Walvoord also explains that while it is too complex to study the benefits of assessment on a national scale, within specific institutions there are numerous examples of how assessment is “used as a tool to help faculty and institutions make decisions that affect student learning” (p. 10). She argues that informed decision-making is perhaps the best benefit of assessment and why it has such potential to help improve teaching and learning.

Activity: From Application to Practice

Four scenarios appear below that describe potential situations in which higher education professionals may be asked to explain the benefits of assessment. Select the scenario most likely for your current role and create a response based on the directions in the prompt.

1. The Committee Reassignment

You are a tenured faculty member and currently the assessment coordinator for your department. Your Dean has asked whether you would be able to serve on a different committee and put the department’s assessment work “on hold” for a few years. Write an email to your Dean explaining why your current assessment work is important and why it is beneficial for you to maintain this assessment role for students, your colleagues, and other stakeholders.

2. The Board Presentation

As director of assessment, you are asked to give a 15-minute presentation to the Board of Trustees (which has a number of new members who are new to academia), explaining what student learning assessment is and what the benefits of this work are to improving teaching and learning at the institution. Create an outline with your key talking points in preparation for this presentation.

3. A Curmudgeonly Colleague

During one of your department’s weekly faculty meetings, one of your colleagues is complaining about the time and effort needed to complete that year’s assessment report. After the meeting, you learn that the chair has tasked you and the curmudgeonly colleague with writing and sharing this year’s report. Write an email to this colleague, sharing the news of the assigned task and getting him/her “on board” with the assignment by explaining why this work is an important use of time.

4. Budget Request

You are the Dean of your school, and you are preparing a budget for the next fiscal year that includes a request for additional resources for assessment (including a new line for an administrative assistant, funding for an annual assessment retreat, and resources for professional development). Write a paragraph arguing why these requests are justified and a worthwhile use of limited funds.

Final Reflection: After completing the activities, reflect on your final product by responding to the questions below. You can do this exercise through either individual reflective writing or discussion with a partner.

- While creating the final product, on which points did you decide to focus and why?

- What questions or challenges arose for you when completing this task?

- For group dialogue: What is one piece of advice or information that you would give your colleague if they asked for feedback on how to strengthen the argument in their final piece?

Resources

Walvoord, B. E. (2010). Assessment clear and simple: A practical guide for institutions, departments, and general education. (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Chapter 2: What is the purpose of assessment?

Warm Up Activity: What has been your direct experience with gathering assessment data?

Open the following file: Possible Experiences with Gathering Data

Check off all of the activities from the list that you have done before and write down other tasks that you have completed that do not appear on the list.

Possible experiences with gathering data:

- Designed an assessment instrument to be used to evaluate student learning in an individual class, such as rubric, essay prompt, or multiple-choice exam.

- Used an assessment instrument to evaluate student learning in a single class.

- Used short, ungraded activities during class to collect data on student learning (brief response writing, clickers, etc.).

- Designed an assessment instrument to be used to evaluate student learning across multiple sections of a single class.

- Used an assessment instrument to evaluate student learning across multiple sections of a single class.

- Collected samples of student work from multiple classes to evaluate for assessment purposes.

- Engaged in sampling student work (aka, randomly selecting 15% of student essays from the sophomore class).

- Helped design an assessment plan for your department, school/college, or general education.

- Helped design or manage the electronic collection of assessment data, such as through an e-portfolio.

Now that you have reflected on how you have engaged with gathering assessment data, it is time to consider why different people invest the time and effort into these activities. Below, you will find a chart in which different stakeholders at one institution have explained the top three reasons why they gather assessment data.

Review this chart and then answer the reflection questions.

| Role in Institution | Purpose of Gathering Data |

|---|---|

| Faculty Member | Monitor progress, evaluate learning outcomes, and identify student needs. |

| Department Assessment Coordinator | For continuous improvement to our curriculum, programs, and services; to better understand our students; and for compliance with accreditation standards. |

| Department Chair |

To assess the degree to which students learned and could apply the concepts taught in class. To assess whether teaching methods met the different learning styles of the students. To identify areas of teaching (or topics covered) that students felt could be improved-their comments help with figuring out how they can be potentially improved. |

| Director of Assessment |

I gather data to give our institution insights into the strengths and weaknesses in student learning that need to be addressed through curricular revisions. Data also provides individual programs with data on how their students are learning to support their self-studies, accreditation reporting and curricular revisions. It also provides individual programs and the institution as a whole with data on how students are learning to act on and report those actions as part of our institutional accreditation process. |

| Faculty Chair of Institution-Wide Assessment Committee | I gather assessment data to gain feedback on my teaching and make data-based decisions. If student learning is strong, I keep doing what I’ve been doing. If my data show there are weaknesses in student learning, I make curricular and pedagogical changes to improve student learning. |

| Associate Vice Provost for Assessment |

OR:

|

| Director of Teaching Center | Collecting assessment data on student learning helps us decide on what types of teaching workshops to offer to faculty. It also helps us coach faculty members to see the “bigger picture†of student learning so that they can make wise choices when revising a course or deciding whether to implement a new teaching strategy. Assessment helps us see whether changes should be made at the course or the curriculum level. |

| General Education Director |

As we roll out a new program, collecting assessment data has allowed us to tweak classes each year, preventing the entrenchment of ineffective practices. Embedded assessment is a reassuring and important component of the new program for faculty. We can demonstrate that curricular oversight is happening and leading to change, when necessary. |

| Dean with External Accrediting Body |

I gather data to: Help insure each of the departments within my division are satisfying their assessment requirements to support programmatic and institutional accreditation. Justify proposals for new grant funding or for reporting on existing grants using student learning data. Provide data on our divisional contributions towards individual goals within the Strategic Plan that can be evaluated using learning assessment data. |

| Provost |

I gather data to: Evaluate specific academic initiatives such as the redesign of our developmental mathematics pathways. Ensure that we are meeting our institutional accreditation requirements for assessment. As a state institution, we also utilize assessment data to respond to system-wide initiatives or inquiries for the Department of Higher Education. |

Activity: Reflecting on Shared Experiences

After reviewing the chart, write reflective responses to, or with colleagues discuss the following questions:

- Find the role that most closely matches your own. Do you agree with the insights shared in the example? Did anything strike you as similar to or different from your own experience?

- What are some points that are missing from this list?

- What are three other stakeholders who could be added to this list? What would be their top purposes for gathering data?

- For each of the roles above, consider who benefits from their purpose of gathering data. Are the benefits what you would expect or hope for? Is anything missing?

Research on the Purpose of Gathering Assessment Data

In Assessing Student Learning: A Common Sense Guide (2nd Ed.), Linda Suskie divides the purposes of gathering student learning assessment data into two broad categories: improvement and accountability (p. 58).

The following list draws from Suskie (p. 58-61), Maki (p. 20-22), and the authors’ experiences to organize purposes for gathering assessment data by stakeholder type:

Improvement

Purpose for Students:

- To help them understand how to focus their time and energy around learning.

- To motivate them to perform well.

- To understand their strengths and weaknesses.

- To keep stock of and reflect on their progress as learners.

Purpose for Faculty:

- To facilitate discussion on what you teach and why.

- To clarify common expectations and performance standards.

- To encourage a collaborative approach to improving teaching.

- To create alignment between and among courses.

- To inform future and ongoing research on teaching.

- To make informed decisions about how to use limited resources.

Purpose for Academic Leadership and Curriculum Improvement:

- To improve the coherence of academic programs.

- To create benchmarks for future analysis.

- To add insight into how the sequencing of courses impacts learning.

- To provide feedback to help faculty decide if and how the curriculum should be changed.

- To bring “neglected issues to the forefront,†such as “outdated general education curricula . . . a fragmented and incoherent curriculum, or outmoded pedagogies†(Suskie, 2009, p. 59).

- To improve institutional structures and effectiveness.

- To educate institutional stakeholders about the results of new initiatives or changes in academic programs.

- To inform strategic planning and institutional budget decisions.

Accountability

Accountability involves demonstrating the quality and effectiveness of the current curriculum, teaching, and learning to “concerned audiences†(p. 58). These can include external audiences, such as regional accrediting organizations and discipline-specific accrediting organizations (often for professionally-oriented programs such as business, social work, or nursing). Other external audiences can include legislatures, external funders, parents, prospective students, and the general public. Internal audiences include governing boards, assessment oversight committees, and various levels of leadership within the organization.

Activity: Application to Practice

Now that you have reviewed research and an example from colleagues on the purpose of gathering assessment data, it is time to apply these principles to your own institutional context. In the chart below, first brainstorm any stakeholders at your institution or within your unit (school, department, etc.) that would have a purpose for gathering assessment data. Then, in the second column, for 3-4 of these stakeholders, list the types of decisions that they would be making with assessment data or the types of purposes that they would have for gathering data. Open the Activity Worksheet to record your answers.

| Role in Institution | Purpose of Gathering Assessment Data |

|---|---|

Final Reflection

After completing the activities, reflect on your final product by responding to the questions below. You can do this exercise through either individual reflective writing or discussion with a partner.

- While reviewing your list of stakeholders, did you notice any differences between what you included or did not include and those included on the sample chart? Why do you think you included the people who you did?

- How did the purposes for gathering data vary (or not vary) by the person’s role within the institution?

- For group dialogue: Compare your chart with a colleague’s. What similarities and differences do you see? Why?

Resources

Maki, P. L. (2010). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution. (2nd ed.). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Suskie, L. (2009). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Chapter 3: Why are assessment data useful?

Warm Up Activity: Respond to the following questions through either individual reflective writing, or small group discussion:

- How have you used assessment data in the past? In what context?

- How was it useful?

- What decisions did it help you or your department make?

This video shares the experiences of different faculty members and administrators on the usefulness of assessment data in informing decision-making, curricular change, and improving teaching and learning in each of their respective roles.

Activity: Reflecting on Shared Experiences

After watching the video, write reflective responses to, or with colleagues discuss the following questions:

- What were some of the key themes that you heard/saw in the videos?

- Which uses on your list were also mentioned by the faculty and administrators in the video?

- Which benefits mentioned in the video were not on your initial list? Did these benefits surprise you? If so, why?

- Did the distinct positions (director of assessment, dean or chair, and faculty member) benefit differently from assessment? How did they use data similarly or differently?

If you have generated additional ideas after watching and reflecting on the video, please add them to your initial Warm Up exercise.

Research on Why Assessment Data are Useful

The Usefulness of Assessment Data

Suskie (2009) explains that there is a lack of published research on the usefulness of assessment data because assessment is “context specific rather than generalizable, informal rather than rigorous, and designed to inform individual rather than general practice†(p. 60). Because this work is not published in peer-reviewed journals, “there is no way that the hundreds, if not thousands, of these kinds of success stories can be aggregated†(p. 61), although there are a few books containing collections of case studies (Banta, Lund, Black, & Oblander, 1996; Bresciani, 2006, 2007). However, as Suskie notes, these institution-specific uses of assessment data are happening on a regular basis.

Rather than delve into institution-specific examples, we have listed below the types of decisions that are often made using assessment data. This is only a sample of the many possible uses of assessment data.

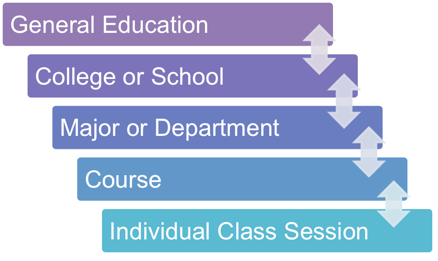

The usefulness of assessment data can also be thought of in terms of the level of the curriculum that it has the potential to impact or change. Assessment data is typically collected at multiple levels for that reason:

Often, data collected at a specific level is used to impact change within that level. However, many institutions collect and review data on institution-wide learning objectives (such as writing or critical thinking, for example) from across multiple levels of the institution in order to inform institution-wide decisions, such as General Education reform, topics for faculty professional development, or allocation of resources for new or enhanced student services.

Activity: Application to Practice

Create a list of at least ten possible uses of assessment data for your particular role at your institution. Try writing them as questions that you might want to have answered, and try to be as specific as possible. These do not necessarily have to be questions that you would answer now, but that you might need to answer at some point in the future in your role. Here are some examples of possible questions:

- Should we reduce the maximum class size in Writing 101 from 18 to 15 students?

- Should we rehire the adjunct faculty member to teach two sections of Introduction to Biology in the Spring?

- Are the first two courses in the Philosophy major in the right sequence?

- What topics should we focus on for our department’s professional development day?

- Are enough students demonstrating sufficient competency in their understanding of medical calculus, or do we need to add a required 1-hr course to the curriculum?

- Is my lesson plan from today effective?

Next, for each of your ten questions, write down a piece of assessment data that you think might be most useful to you in answering that question.

Final Reflection

After completing the activities, reflect on your ten questions by responding to the questions below. You can do this exercise through either individual reflective writing or discussion with a partner.

- While reviewing your list of questions, did you notice whether they tended toward improvement or accountability? Were your questions focused on improvement within the classroom, major or department curricular issues, personnel or resource decisions, or another area?

- Were your questions focused on improving a certain level of the institution (aka, classroom-level, department-level)?

- What types of data did you identify as being helpful and why? Are these types of data collected already by your institution?

- For group dialogue: Compare your questions with a colleague’s. What similarities and differences do you see? Why?

Resources

Banta, T. W., Lund, J. P., Black, K. E., & Oblander, F. W. (1996). Assessment in practice: Putting principles to work on college campuses. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bresciani, M. J. (2006). Outcomes-based academic and co-curricular program review: A compilation of institutional good practices. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Bresciani, M. J. (Ed.). (2007). Assessing student learning in general education: Good practice case studies. Bolton, MA: Anker.

Chapter 4: What are some concerns about assessment?

Warm Up Activity:Â Generate a list of issues and concerns about the assessment process that you have frequently heard raised on your campus.

![]()

The video shares the experiences of different faculty members and administrators on the usefulness of assessment data in informing decision-making, curricular change, and improving teaching and learning in each of their respective roles.

Activity: Reflecting on Shared Experiences

After watching the video, write reflective responses to, or with colleagues discuss the following questions:

- What were some of the key themes that you heard/saw in the video?

- Which issues or concerns on your list were also mentioned by the faculty and administrators in the video?

- Which issues or concerns in the video were not on your initial list? Did these barriers surprise you? If so, why?

- Did the individual positions (director of assessment, dean or chair, and faculty member) struggle with assessment? Did they encounter different types of barriers?

If you have generated additional ideas after watching and reflecting on the video, please add them to your initial pre-writing exercise.

Research on the Barriers to Assessment

A wide variety of common barriers to effective assessment practices have been enumerated in the literature (Bresciani 2006, Bresciani et al. 2004).

1. Building a campus culture of assessment

While assessment concerns are often described in terms of the threat they represent to academic freedom and academic autonomy, these issues often mask a lack of shared understanding of why and how the campus or department is engaging in the assessment process in the first place. Faculty staff and administrators may struggle with:

- Understanding what it is

- Not knowing how to do it

- Not prioritizing values/goals

- Fear of change, of unknown

- Confusion

- Avoiding being labeled as “one of themâ€

2. Establishing institutional support for assessment

Time is often cited as the biggest barrier to many of our campus initiatives. Assessment is no different and in fact may present greater issues as it is often seen as being “added on†to the regular responsibilities of faculty and staff. While this may be addressed in part through building a more effective campus culture of assessment, issues related to time, resources and the incentives for engaging in assessment can include among other things:

- Finding Time to engage

- Finding time to document

- Getting support from top leadership

- Lack of organizational incentives

- Concern over faculty contracts – a.k.a. – unions

3. Developing strategies to collect data

Even with the commitment and resources necessary, effective assessment presents additional challenges as faculty and staff must gather useful data about student learning. The barriers to collecting data can include:

- Difficulty with requesting data

- Difficulty with finding data

- Lack of truly authentic instruments and evidence- gathering techniques

4. Effectively interpreting and analyzing data

Once assessment data has been collected, there are often challenges associated with making meaning of the data. The challenges of understanding how to work with data that may involve small sample sizes and non-standardized sampling techniques can include:

- Difficulty in identifying how to use data

- Difficulty interpreting data

- Challenge of benchmarking against external standards

- Concern over student motivation and involvement

5. Finding ways to use data for improvement

As we come to terms with any meaningful patterns and potential limitations in the data we have collected, we often also struggle with using this data to inform changes on our campuses, in our departments and in our courses. The barriers to making these changes can include:

- Not using results to inform decision-making

- People who prefer anecdotal decision-making

- Lack of communication about what has been learned

6. Sustaining the assessment process

Finally, while it is important to establish institutional support, it is also critical to maintain that support in order to establish ongoing, effective assessment. In addition to maintaining institutional support it is critical to address issues related to:

- Challenge of managing the assessment process

- Avoiding burnout

Activity: Application to Practice

Struggling with Assessment

Four scenarios appear below that describe potential situations in which a campus is struggling with assessment. Select the scenario most likely for your current role and identify some of the potential issues that may have been affecting the outcome in that scenario. Draw on any of your experiences and the range of issues discussed previously and discuss what could be done to address the issue(s).

1. The Cranky Committee

You are a tenured faculty member and currently the assessment coordinator for your department. You have just completed an assessment cycle and have shared the data you collected with the curriculum committee. At the meeting committee members complained that this was a waste of time, that they could not see how this data would be useful to them, and that it did not offer them anything they did not already know.

2. The Difficult Department

As director of assessment, you are asked to work with a department that is struggling to get its assessment system in place. As you go to meet with the department, you are faced with difficult questions about why they should be engaging in this work in the first place, what is in it for them, and how on earth they can be expected to quantify something like student learning when after all, they know it when they see it.

3. A Curmudgeonly Colleague (continued from Chapter 1)

During one of your department’s weekly faculty meetings, one of your colleagues is complaining about the time and effort needed to complete that year’s assessment report. You have tried to explain to the colleague the benefits of engaging in this assessment work, but the colleague cannot get past the idea that this responsibility has been foisted on them when they have so many more important things to do.

4. Budget Request (continued from Chapter 1)

You are the Dean of your school, and you prepared a budget for the next fiscal year that included a request for additional resources for assessment (including a new line for an administrative assistant, funding for an annual assessment retreat, and resources for professional development). However, this request was not funded. Little explanation was offered other than that the overall budget is tight and resources needed to be used in more effective ways.

Final Reflection

After completing the activities, reflect on your final product by responding to the questions below. You can do this exercise through either individual reflective writing or group discussion.

- As you considered what might be creating the barrier to assessment in the scenario, on which potential issues and challenges did you decide to focus and why?

- What questions or challenges arose for you when completing this task?

- For group dialogue: What is one potential issue or challenge that might be contributing to the outcome in the scenario that your colleague did not discuss?

Resources

Bresciani, M. J. (2006). Good Practices in Outcomes-based Assessment Program Review. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Bresciani, M. J., Zelna, C. L., & Anderson, J. A. (2004). Techniques for Assessing Student Learning and Development in Academic and Student Support Services. Washington D.C.: NASPA.

Chapter 5: What are steps that an institution can take to make assessment useful?

Warm Up ActivityÂ

Think about the assessment processes that take place on your campus. What works well that has allowed your campus to benefit? What has not worked as well that has caused some of the concerns raised in the previous section?

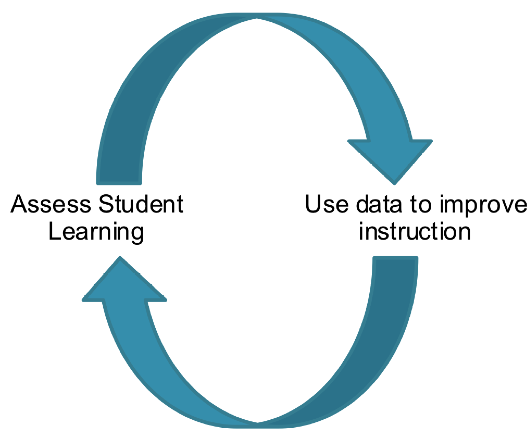

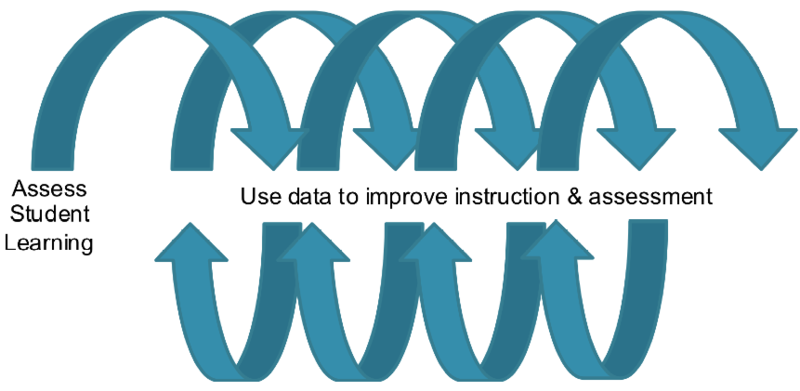

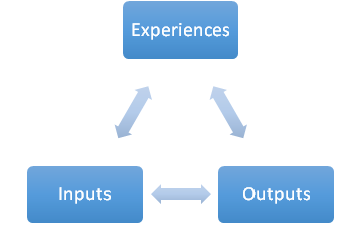

Cycle of Inquiry

The assessment process is frequently represented as a loop or “cycle of inquiry†in which institutional contributors reaffirm agreement about what they want to uncover with regard to student learning, and how to gather, represent, and interpret appropriate data collectively. Institutional contributors then collaborate to innovate teaching and learning processes before reentering the assessment cycle to evaluate those changes (Maki 2010). Assessment is truly useful to a campus when it involves this full cycle of inquiry, culminating in innovations for teaching and learning. The potential barriers to effective assessment organized in the prior section can be further subdivided into those that represent individual elements of the cycle of inquiry leading to improvement, and those that are essential for maintaining the cycle of inquiry:

Elements of the Cycle of Inquiry

- Developing strategies to collect data

- Effectively interpreting and analyzing data

- Finding ways to use data for improvement

Maintaining the Cycle of Inquiry

- Building a campus culture of assessment

- Establishing institutional support for assessment

- Sustaining the assessment process

While the Cycle of Inquiry can be portrayed as a closed loop, (and in fact, the process of reentering the assessment cycle once changes have been made in response to assessment data is often termed “closing the loop,â€) maintaining the cycle of inquiry, and in particular sustaining the assessment process, requires revisiting and revising the way things are assessed on an ongoing basis.

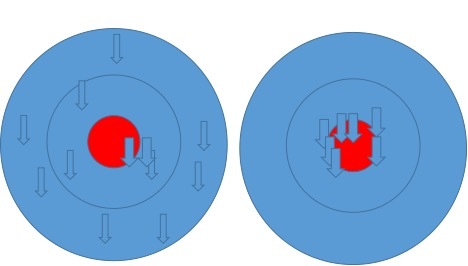

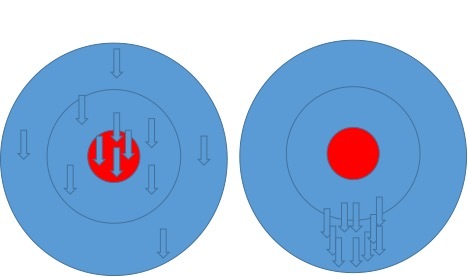

At its most basic, the closed loop of assessment can be represented as follows:

In contrast, when viewed as an ongoing cycle of inquiry that must be revisited and revised in new ways it can be represented as follows:

Activity: Reflecting on What Does and Does Not Work On Your Campus

Consider what you wrote in your initial reflection and write reflective responses to, or with colleagues discuss the following questions:

- What works on your campus that can be considered part of the elements of the cycle of inquiry?

- What does not work well on your campus that can be considered elements of the cycle of inquiry?

- What works well on your campus that helps to maintain the cycle of inquiry?

- What does not work well on your campus to maintain the cycle of inquiry?

Case Studies

The following are case studies of how institutions have attempted to improve the cycle of inquiry (to be included as separate linked documents). As you read these, reflect on the changes they made that improve, support, or maintain the cycle of inquiry. You may also want to brainstorm things they did not do, but could have done to improve the cycle of inquiry.

Case Study 1: Building a Campus Culture of Assessment through Institutional SupportÂ

Case Study 2: The Multi-State Collaborative for Learning Outcomes Assessment

Case Study 3: Finding Sustainable Ways to Use Data for Improvement

Activity: Application to Practice

Using the lists of ways to improve the cycle of inquiry and overcome potential barriers that you generated as you read the case studies, create a list of at least ten possible steps you might take to improve the cycle of inquiry from your particular role at your institution. Try grouping this list into categories of either improving or supporting the cycle of inquiry.

Final Reflection:Â

After completing the activities, reflect on your ten questions by responding to the questions below. You can do this exercise through either individual reflective writing or discussion with a partner.

- While reviewing your list of possible steps, did you notice whether they tended toward improving steps of the cycle or improving support for the cycle?

- Were your steps focused on improving a certain level of the institution (aka, classroom-level, department-level)?

- For group dialogue: Compare your steps with a colleague’s. What similarities and differences do you see? Why?

Resources

Maki, P. L. (2010). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution. (2nd ed.). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Conclusion and resources

Summary of Key Points

Benefits of Assessment

- Informed decision-making is one of the best benefits of assessment.

- Three common actions resulting from assessment-informed decision-making include curricular changes, policy changes, and faculty development.

- There are a variety of examples of how assessment is beneficial within specific institutions.

- Different institutional stakeholders find assessment to be beneficial in different ways, depending on their role within the institution.

Purpose of Gathering Assessment Data

- Different stakeholders vary in their reasons for gathering assessment data.

- The purposes of gathering assessment data can be divided into two broad categories: improvement and accountability.

- Improvement includes helping students improve as learners, helping faculty improve as teachers, and helping academic leadership improve curricula and academic programs.

- Accountability involves demonstrating the quality and effectiveness of the current curriculum, teaching, and learning to both external and internal audiences.

Usefulness of Assessment Data

- Different stakeholders find assessment data to be useful to their work in different ways.

- The usefulness of assessment data is specific to institutional context and individual practice.

- Assessment data is useful in impacting a curriculum at multiple levels, from an individual class session to the General Education curriculum.

- Data collected at a specific level is usually used to impact change within that level, although data can be collected across multiple levels to inform institution-wide decisions.

Concerns about Assessment

- Assessment is often perceived as unfamiliar, confusing, new, unimportant and “someone else’s job†impeding the development of a campus culture of assessment.

- Assessment is not always given the time and attention needed, or the resources and incentives through campus leadership, promotion and tenure decisions and union contracts.

- Campuses often struggle with determining where and how to collect the necessary assessment data, and find that the existing assessment instruments available don’t accurately capture what their students know and can do.

- Campuses may struggle with reaching consensus on the meaning of the data given concerns over the instruments used, the students sampled, identifying appropriate levels of student learning, and the level of engagement of students.

- Campuses may fail to incorporate the data into their decision-making processes, weighting anecdotal data more heavily than the assessment data, and failing to communicate the assessment data effectively across the campus.

- Assessment is often engaged in sporadically rather than systematically on a campus, creating bouts of intense but unsustainable activity and ultimately burnout.

Making Assessment Useful

- Assessment should be viewed as an ongoing cycle of inquiry into student learning in which the assessment data is used both to improve teaching and learning and to improve the assessment process itself.

- Improving the cycle of inquiry can involve both improving the individual steps of the cycle and creating campus policies and procedures that help to maintain that cycle of inquiry over time.

- Improving the steps of the cycle can involve improving the approaches to collecting data, the analysis, interpretation and communication of the data, and the ways the data is used for improvement.

- Improving the support for the cycle of inquiry can involve creating a culture of assessment, improving institutional support for assessment and insuring that this support and campus climate is properly sustained over time.

Reflection

- Return to your list of assessment benefits. Which are the most relevant for your particular role? How can you remain mindful of this list as you do your assessment work?

- Reflecting on the purposes for gathering data, did you discover a purpose for your work that you had not previously considered? How can you begin gathering data for this purpose?

- What were your insights into why people in other roles gather data at your institution? In what ways did this shed light on why certain processes happen at your institution?

- Write three questions that assessment could be useful in answering.

- Identify three of the biggest barriers to assessment that you face at your institution.

- If you were to do something to improve assessment at your institution, what would be your first three steps?

Cited & Additional Resources

Banta, T. W., Lund, J. P., Black, K. E., & Oblander, F. W. (1996). Assessment in practice: Putting principles to work on college campuses. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bresciani, M. J. (2006). Outcomes-based academic and co-curricular program review: A compilation of institutional good practices. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Bresciani, M. J. (Ed.). (2007). Assessing student learning in general education: Good practice case studies. Bolton, MA: Anker.

Maki, P. L. (2010). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution. (2nd ed.). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Suskie, L. (2009). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Walvoord, B. E. (2010). Assessment clear and simple: A practical guide for institutions, departments, and general education. (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Introduction

Demystifying Assessment Facilitation Guide

LARC Beta-Testing Institutional Example 1

LARC Beta-Testing Institutional Example 2

LARC Beta-Testing Institutional Example 3

Audience

This module offers an introduction to the vocabulary of assessment in higher education. It is intended for three main audiences: faculty, staff, administrators, as well as other institutional stakeholders who:

- Consider themselves new to the assessment conversation;

- Are already involved in assessment efforts, but would like to strengthen their understanding of assessment terminology; and/or

- Have an advanced understanding of assessment, but who are charged with training or educating their peers and colleagues about assessment.

Goals

This module is designed to help participants:

- Recognize their current involvement in assessment activities.

- Learn basic assessment terminology and how it varies from institution to institution.

- Determine what assessment language is appropriate for their institution.

- Analyze differences and similarities between assessment, grading, and evaluation.

- Understand the foundational frameworks related to assessment.

Objectives

Upon completion of this module, participants will be able to:

- Define assessment.

- Articulate the differences between assessment and evaluation.

- Differentiate between assessment and evaluation activities.

- Define terminology related to assessment.

- Define terminology related to data gathering methods and tools.

- Compare foundational frameworks for assessment commonly used in higher education.

Chapter 1: What does assessment mean?

Warm Up Activity

Whether you are a faculty member, department chair or assessment director, you have been involved in assessment in one way or another. As a warm up to this module, consider some of the assessment activities that you already do.

Using the chart below, indicate whether you or someone on your campus is completing any of the following. Use the Comment column to add clarifying language. For example, if you are unsure of what the term means or if you plan to complete this activity in the future, make a note.

| Activity | We Do This | We Don’t Do This | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Establish clear, measurable learning goals and objectives. | |||

| Align course, program and institutional learning goals and objectives. | |||

| Ensure that students have multiple opportunities to meet the learning objectives. | |||

| Ensure that learning objectives are mapped to courses for different levels of expertise. | |||

| Systematically collect evidence that students are meeting course learning objectives. | |||

| Analyze collected evidence to understand how well students are meeting learning objectives. | |||

| Use analysis of evidence to redesign learning activities to increase the likelihood that students will meeting learning objectives. | |||

| Require assessment in program review. | |||

| Embed assessment of learning in institutional initiatives (retention, technology, online learning, learning communities). | |||

| Review course goals and objectives to meet professional standards. |

How do you already “do assessment�

“Assessment is the systematic collection of information about student learning, using time, knowledge, expertise, and resources available, in order to inform decisions that affect student learning†(Suskie, 2010, p. 2).

The good news is that assessment is not a new activity; it is something that educators do naturally, and it is not unusual for faculty to reformulate learning activities as a result of unexpectedly poor results of a formative or summative assessment. Ask yourself:

- When was the last time you were completely satisfied with student performance?

- When was the last time you did not tweak your course in some way?

- Why did you make these changes?Â

Perrine et al (2010) likens assessment to cooking: if you prepare a dish and it does not taste just right, how do you go about assessing the changes that need to be made to improve the dish? In assessment language, the changes you make to improve the dish are referred to as “closing the loop.â€

Closing the loop is another way of describing “informed decision-making,†which Barbara Walvrood (2004) suggests is the best benefit of assessment and why it has such potential to help improve teaching and learning. These improvements can range from a simple change to a course activity to complex changes in programs of study, policies that support student learning, and faculty development. For a more detailed explanation, refer to the Assessments Benefits & Barriers module.

In order “to do†assessment at the institutional, program, and course level, we connect the outcomes to intended goals and objectives of learning; that is, what do we want our students to know, apply, or be able to do. As was mentioned earlier, many of you are most likely doing assessment on this wider scale. Using the table below, create an inventory of assessment activities you are doing on your campus. If you are unsure, invite others to join in on this activity.

Activity: How are you already collecting evidence?

How are you already collecting evidence that your students are meeting the institutional, program, and course levels? Using the table below, check the items that apply and indicate at what level the evidence applies.

| Activity | Course Level | Program Level | Institutional Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Survey of student engagement | |||

| Final exams | |||

| Student presentations | |||

| Internship | |||

| Service-learning activity | |||

| Portfolios | |||

| Poster presentation | |||

| Multiple choice tests | |||

| Student surveys | |||

| Reflective writing | |||

| Class discussions | |||

| Admission rates to graduate school | |||

| Holistically scored writing sample | |||

| Focus groups |

What does it mean to assess student learning?

Linda Suskie (2009, p. 4) suggests that there are three components to assessing student learning:

- Establishing clear, measurable learning objectives

- Ensuring that stakeholders have sufficient opportunities to achieve objectives

- Systematically gathering, analyzing, and interpreting evidence to determine how well courses, practices, programs, or initiatives match expectations

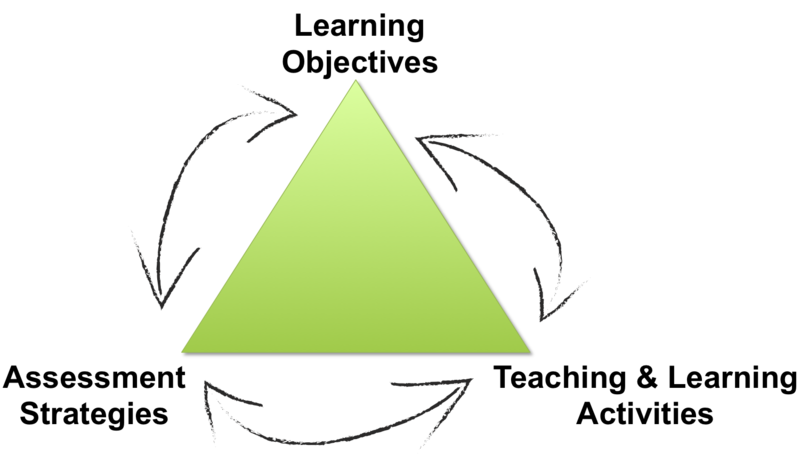

Establishing clear, measurable learning objectives is an effective way to connect what students are learning to the larger picture established by the goals of the course, the program, and the institution. You may recall from the Goals and Objectives module that learning objectives describe what students will do as a result of the teaching and learning activities.

Learning objectives should answer the question:Â what is it you want your students to be able to do as a result of the course activities that will provide evidence that they have met the specified learning goal?

See Five Concepts to Remember in the Goals & Objectives module for common mistakes to avoid when preparing learning objectives.

Activity: Establishing Clear, Measurable Learning Objectives

Considering your role (faculty, department chair, assessment director), how would you assess student learning in your course, program, or institution?

Use the form below to outline clear, measurable learning objectives:

| Course, Program, or Initiative | Goal: Upon completion of this course, students will know/understand: | Objective: Students will be able to: |

|---|---|---|

|

EXAMPLE: (Course) Business Communications Course |

How to deliver effective written communications | Prepare a business report that is clear, logical, concise, grammatically correct, and targeted to a specific audience |

Ensuring that stakeholders have sufficient opportunities to achieve learning objectives could be accomplished through scaffolded assignments that begin by targeting low-level learning skills and progressively engage higher-level learning skills. A commonly used resource for identifying observable and measurable action verbs, while considering different cognitive levels and knowledge dimensions, is Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Refer to Bloom’s Taxonomy as you determine how to scaffold learning activities associated with meeting learning objectives in the following activity.

Activity: Ensuring Multiple Opportunities to Achieve Learning Objectives

What are the learning opportunities associated with a particular learning objective? In the example below, notice the range of learning activities. Consider what students need to be able to accomplish first (lower level thinking skills) before they are able to apply (higher level thinking skills) what they have learned. Use the form below to list learning opportunities that are designed to scaffold learning for your students in your course, program, or institution.

| Objective: Students will be able to: | Thinking Skills – Lower Level | Thinking Skills – Higher Level |

|---|---|---|

|

EXAMPLE: Prepare a business report that is clear, logical, concise, grammatically correct, and targeted to a specific audience |

-Define audience -Outline argument -Rewrite a sentence to make it concise -Edit paragraph for grammatical errors |

-Write a thesis statement -Develop a plan for a business report -Prepare a rough draft of the business report -Peer review a business report |

Systematically gathering, analyzing, and interpreting evidence to determine how well courses, practices, programs, or initiatives match expectations will not only help you evaluate student learning, but these steps will also be instrumental as you decide what adjustments need to be made to your course, program, or institutional goals, outcomes, learning activities or assessments.

The gathering of assessment data takes careful planning before the learning experience begins. Assessment data can be generated throughout the learning experience and the data could be collected at any time before, during, and after the learning experience. A number of practical considerations also have the potential to impact the assessment process.

Some factors to consider when looking at assessment data are more fully explained in the Gathering Data module:

- Prioritize the evidence you are gathering

- Consider how the evidence you’ve gathered contributes to the broader campus-wide body of knowledge

- Look for a possible link to accreditation and regional assessment needs

When analyzing the data, consider:

- Factors that are related to the relevance of data

- The controllability of the data

- The quality (reliability and validity) of the data

Linda Suskie (2009) suggests a “toolbox†of assessment instruments (exams, reflections, interviews, focus groups, etc.), because of their unique data gathering capabilities, will produce very different types of data . To get a more detailed understanding of data gathering processes, complete the Gathering Data module.

Activity: Gathering Data Through Assessment

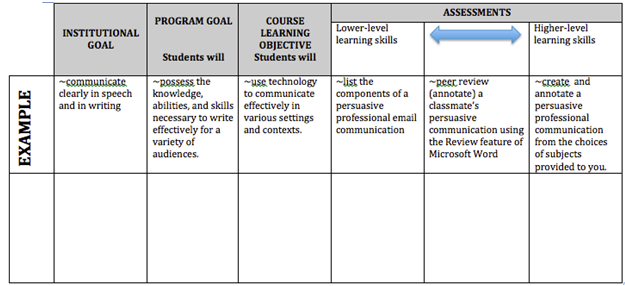

How will you collect evidence that reflects how your students have met the learning objectives of the course, program, and/or institution? Use the form below to show the link between institutional goals, program goals, and course learning objectives and assessments that span levels of learning skills.

NOTE: It is helpful to differentiate between assessment and grading:

- Grading focuses on individual students

- Assessment focuses on the entire cohort or class of students.

The next sections will elaborate on why grades alone will not yield the information that is needed to fully assess the learning of students in your course, program or institution.

Final Reflection

Now that you have had a chance to articulate what you already know about assessment by completing the exercises in this section, consider the difference between assessment of learning and grading. Think of a past assignment that you have either administered to your students or completed as a student.

- How well did the grade reflect how students met the learning objectives related to the assignment?

- Is there an additional way that you could have collected and analyzed the evidence that would have led to information about how well the learning objectives were met?

Resources

Maki, P. L. (2010). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Maxfield, L. (2010). Assessment is like a box of chocolates. In P. L. Maki (Ed.), Coming to terms with student outcomes assessment: Faculty and administrators’ journeys to integrating assessment in their work and institutional culture. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Perrine, R., Sweet, C., Blythe, H., Kopacz, P., Combs, D., Bennett, O., Street, S., & Keeley, E. (2010). The transformation of a regional comprehensive university. In P. L. Maki (Ed.), Coming to terms with student outcomes assessment: Faculty and administrators’ journeys to integrating assessment in their work and institutional culture. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Suskie, L. (2009). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Walvood, B. (2004). Assessment clear and simple. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Chapter 2: How is assessment related to evaluation?

Warm Up Activity

Check your understanding of assessment and evaluation. Which of the below do you identify as assessment and which do you identify as evaluation?

Self Assessment Activity

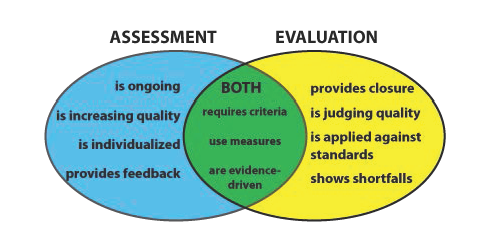

Differences and Similarities Between Assessment and Evaluation

Assessment

Assessment is gathering information to make a determination about something (i.e. a measurement of student learning). Assigning a grade to student work is not assessing. The goal of grading is to evaluate individual students’ learning and performance, where the goal of assessment is to improve student learning. Grading may play a role in assessment but there are also many ungraded activities in assessments (e.g. classroom assessment techniques aka “CATS”). Data collection for assessment should correlate directly to clearly defined targets, whether that be objectives or outcomes.

Assessment can happen at the course level, program level, or institutional level:

- Course level: assignments, activities.

- Program level: capstone experiences, field experiences, portfolios.

- Institutional level: competencies typically integrated in general education curriculum, majors, and student development programs.

Assessment activities include the continuous process of:

- Establishing clear, measurable learning objectives.

- Ensuring students have opportunities to exhibit achieving the learning objectives.

- Systematically collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data.

- Using data interpretations to increase the quality of learning.

Evaluation

Assessment activities can be useful in and of themselves, but the data becomes more meaningful as part of evaluation. Evaluation is using assessment data to understand (level of success or value), judge, and/or improve current knowledge, services, and/or practices. Evaluation cannot be done well unless the assessment is sound (good assessment leads to good evaluation).

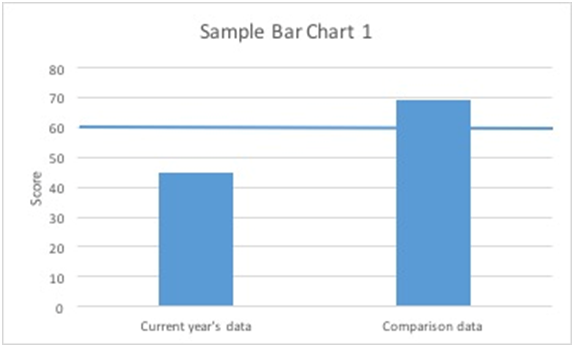

In order for this to happen, there needs to be alignment between assessment and evaluation. While assessment results guide us, evaluation allows us to make decisions. Here is a visual representation so that you can see how assessment and evaluation work together.

Evaluation allows us to answer questions such as:

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of teaching and learning strategies?

- What changes in goals are needed?

- Can we justify the program’s expense?

- What is working well in the program and how can we still improve it?

- Which teaching and learning strategies should we change?

- Have students achieved the established learning goals?

Evaluation is about ‘closing the loop’ in the assessment process. This is typically the most difficult part of the assessment process, and is often abandoned or forgotten. Closing the loop can refer to many different outcomes and actions that result from reviewing the assessment data. Evaluation activities include:

- Reviewing assessment data.

- Drawing conclusions.

- Presenting data to stakeholders to take action.

- Re-evaluating data or outcomes.

- Following-up on implementation of actions agreed upon/required.

Activity: Defining Features Matrix

Now that you have a better understanding of assessment and evaluation, complete the defining features matrix. Categorize the concepts assessment and evaluation according to the presence (+) or absence (-) of the important defining features listed below.

| Features | Assessment | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Requires on-going activity | ||

| Require criteria to make decisions | ||

| Provides closure | ||

| Aims to improve the quality of higher education | ||

| Uses data measurement | ||

| Aims to judge the quality of higher education | ||

| Highlights shortfalls from the data | ||

| Is evidence-based | ||

| Can be individualized |

Features of Assessment – Answers

Implementing Assessment for Evaluation

Good assessment is not a “one-and-done†project. Assessment is an ongoing systematic effort to improve the quality of education. Systematic does not necessarily mean doing the exact same thing every year, however. You cannot conduct assessment the exact same way every time because needs, students, tools, and curricula are always changing. Systematic really refers to having an approach or a plan to assessment that you are working towards continuously. Many of these elements are associated with information in the other assessment modules and are linked below. Here is one example of a systematic approach to assessment adapted from Banta and Palomba (2015):

I. Planning

- Engage stakeholders.

- Identify the purpose of the assessment.

- Create a written plan with milestones over several years for sustainability.

II. Implementation

- Identify leadership at all levels (course, department, program, institutional).

- Identify data collection strategies.

- Develop or purchase appropriate measurement instruments.

- Orient stakeholders to the tools and their role.

- Collect Data.

- Organize and analyze data.

- Summarize findings.

- Share results.

III. Improving and Sustaining

- Evaluate credibility of evidence (performed by stakeholders).

- Improve collection methods, if necessary.

- Review, share, and take necessary actions related to assessment findings (performed by assessment leadership).

- Reexamine assessment plan and processes periodically, and make changes as necessary.

Activity: Reviewing Your Systematic Approach

Using Banta and Palomba’s (2015) example, think about assessment on your campus. Check off the steps that you know are currently happening. Which steps are you missing? Are there additional steps in your process that are not listed here?

Planning

- Engage stakeholders.

- Identify the purpose of the assessment.

- Create a written plan with milestones over several years for sustainability.

Implementation

- Identify leadership at all levels (course, department, program, institutional).

- Identify data collection strategies.

- Develop or purchase appropriate measurement instruments.

- Orient stakeholders to the tools and their role.

- Collect data.

- Organize and analyze data.

- Summarize findings.

- Share results.

Improving and Sustaining

- Evaluate credibility of evidence (performed by stakeholders).

- Improve collection methods, if necessary.

- Review, share, and take necessary actions related assessment findings (performed by assessment leadership).

- Reexamine assessment plan and processes periodically, and make changes as necessary.

Final Reflection

Now that you understand the differences between assessment and evaluation and the tasks involved, how well does your organization score?

Assessment

- Exceeds expectations

- Meets expectations

- Needs improvement

Evaluation

- Exceeds expectations

- Meets expectations

- Needs improvement

If you checked ‘needs improvement’, what tasks need to be addressed? Who can help facilitate this change?

| Task to Address | Who can help with this? |

|---|---|

Resources

Banta, T. W., & Palomba, C. A. (2015). Assessment essentials: Planning, implementing, and improving assessment in higher education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Suskie, L. (2009). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide. (2nd. ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Chapter 3: What basic assessment terminology do I need to know?

Warm Up Activity

Write as many assessment terms as you can in 30 seconds.

Now, with your list of terminology, circle the terms you can confidently define.

Were you able to circle every item? Did you have terms listed that you consistently hear or say but are unable to clearly define? We will cover several common terms in this module.

Are You Confused by Assessment Jargon?

The assessment process can be confusing but the terminology can be even more so. Are you confused by assessment jargon? Is there an assessment term you hear all the time but are unsure exactly what it means?

Here is a list of commonly used assessment terms you should know. There may be several different ways to define the same term—these definitions are what we found in popular literature. While the following definitions are widely accepted it will be important for you to understand and use the terminology as it is defined on your own campus. Consistency is key to assessment!

This is a glossary for your reference. Feel free to scan these terms and definitions as needed.

Activity: Important Terminology in Use

As stated previously, terms may mean different things at different institutions. You can help your assessment efforts by establishing a consistent language around assessment terminology. Think about the terms you just reviewed. Determine which ones you can use as is, which ones need clarification based on your institution’s definition and use, and which terms are missing. You may want to work with a colleague to brainstorm.

Final Reflection

After completing the activities, answer the following questions. You can do this exercise through either individual reflective writing or discussion with a partner.

- How many words/expressions do you think you have acquired?

- Do you think you will be able to understand the meanings when you hear them in a conversation?

- Do you think you will be able to understand the meanings when encountering them in readings?

- Have you used them in speaking or writing?

- What are some strategies you can employ to help you remember important terms at your institution?

Resources

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1994). Classroom assessment techniques. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Banta, T. W., & Palomba, C. A. (2015). Assessment essentials: Planning, implementing, and improving assessment in higher education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Leskes, A. (Winter/Spring 2002). Beyond confusion: An assessment glossary. Peer Review, Washington, DC: AAC&U.

Maki, P. L. (2010). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution. (2nd ed.). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Palomba, C. A., & Banta, T. W. (1999). Assessment essentials: Planning, implementing, and improving assessment in higher education. Higher and Adult Education Series. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Secolsky, C., & Denison, D. B. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook on measurement, assessment, and evaluation in higher education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Suskie, L. (2009). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Chapter 4: What frameworks will help me understand assessment in higher education?

Warm Up Activity

What are some of the methods that you use to collect evidence that students are meeting your course, program, and/or institutional learning objectives? Use the table below to identify the methods used by you and your colleagues on your campus to assess student learning.

| Assessment Methods | Course Assessment | Program Assessment | Institutional Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tests & Quizzes | |||

| Focus Groups | |||

| NCLEX or other licensure exams | |||

| Senior Capstone Portfolio | |||

| Offer of Employment | |||

| Oral Presentation | |||

| Polling |

What frameworks will help me understand assessment in higher education?

“To be meaningful, assessment should provide both students and faculty with information for improvement at both course and program levels†(Palomba & Banta, 1999, p. 69).

Assessment is a process that focuses on student learning in a systematic way and is done on many levels. To find out if students are learning:

- we collect evidence;

- reflect on what the evidence tells us about student learning; and

- review and revise our approaches to teaching and learning when the evidence suggests that students are not learning as we intended.

Data are collected for multiple reasons

Formative and summative assessments can be applied at both the course and program level. At the program level, Palomba and Banta (1999) suggest that we may use assessment data to form the structure of the program. Once the program is formed, we assess data in a summative way to test the effectiveness of the program.

At the course level, formative assessments are built around smaller increments of learning objectives and summative assessments are meant to test how well students met the learning objective as a whole.

Formative assessment happens during the learning process and is described by Bailey & Jakicic (2012) as “an activity designed to give meaningful feedback to students and teachers and to improve professional practice and student achievement†( p. 14).

Summative assessment occurs at the end of the learning process and “is used to give a grade or provide a final measure of students results†(Bailey & Jakicic, p. 14).

Activity: Formative or Summative

In the chart below, determine whether the assessment is formative or summative and describe its purpose.

| Assessment Activity | Formative/Summative | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Clicker (student response systems) | Formative | To give immediate feedback |

| Quizzes | ||

| Presentations | ||

| Concept Maps | ||

| Practice Problems | ||

| Exams | ||

| Discussions | ||

| Self-assessments |

Data are collected using multiple methodsÂ

The following overview of assessment methods is not meant to be exhaustive; rather, it is an introduction to some of the most well known and practiced methods of collecting evidence of learning. Institution, program, and course assessors are encouraged to survey stakeholders and expand upon these methods in ways that meet the learning needs of individual institutions.

Direct and Indirect Methods of Assessment

A meaningful assessment plan includes both direct and indirect methods of assessment. While these terms may look like a dichotomy, it may be more useful to think of the relationship between direct and indirect measures as a continuum. To read more about this line of reasoning, please see Analysis Methods.

Direct methods of assessment are generally thought to be quantitative in nature, while indirect methods are more often thought of as qualitative. In terms of data collection, they complement one another.

- Direct Methods of collecting assessment data “require students to display their knowledge and skills as they respond to the instrument itself†(Palomba & Banta, 1999, p. 11). When you ask students to respond to questions on an exam, you are using the direct method of assessment.

- Indirect Methods of collecting assessment data can be “helpful in deepening interpretations of student learning†(Maki, 2010, p. 213). When you ask students to respond to a survey or participate in a focus group, you are using the indirect method of assessment.

Examples:

Direct Methods of Assessment:

- True/False Test

- Graded Clicker Questions

- Pass Rates on Licensure Exams

Indirect Methods of Assessment:

- Graduation Rates

- Small Group Instructional Diagnosis (SGIDs)

- Interviews

Activity

Direct Methods of Assessment offer evidence by way of actual student work of what students are or are not learning.